Please enter Email

Email Invalid Format

Please enter your Full Name.

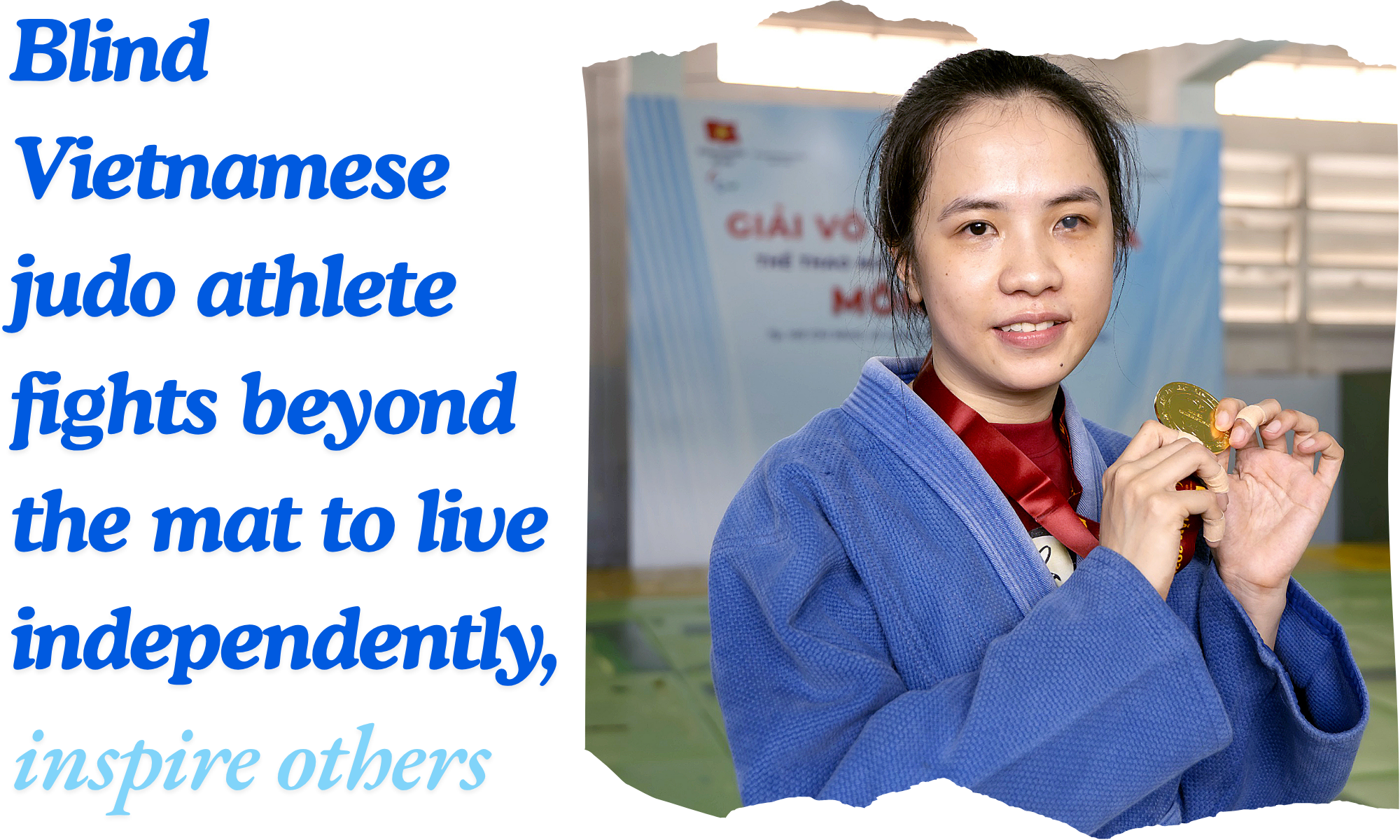

Oanh, who lost her vision permanently after two failed eye surgeries in her teens, is now a national champion in para-judo.

In September, she struck gold in the under-57kg category at Vietnam’s 2025 National Judo Championship for Athletes with Disabilities.

Her sight is gone, but her resolve is sharp.

“I don’t want people to pity me,” she said, adjusting her black belt with the help of a volunteer moments before her match.

“I want to be recognized for what I can do, not what I’ve lost.”

On a humid morning in Ho Chi Minh City’s Hoa Hung Ward, Oanh arrived early to prepare.

She quietly ate a small pastry and began warming up alone while other athletes chatted around her.

Para-athlete Trinh Kieu Oanh holds her judo gold medal. Photo: An Vi

Among 27 blind and visually-impaired competitors, Oanh stood out, not for her medals but for her calm smile and poise.

“I just want to do my best,” she said before stepping onto the mat.

Despite the challenges of competing without sight, relying entirely on touch, reflex, and instinct, Oanh won her preliminary bout after nearly 10 minutes of intense grappling.

Later, she approached her defeated opponent, gently reaching out to grasp her hand in thanks.

“We’re not here just for medals,” Oanh said.

“We’re here to show that even if we can’t see, we can still achieve things through sports.”

Oanh trains two to three times a week, squeezing sessions between shifts as a massage therapist — a trade she learned after leaving her hometown to build an independent life in the city.

Judo, she says, has helped her not only regain physical strength but rebuild her self-esteem.

“Each time I practice, I imagine my opponent’s movements in my head," she said.

"It’s the only way to fight.”

When she received her second gold medal, she did not pose or cheer. Instead, she quietly ran her fingers over its ridges.

“Others can see the color, the shape, the details,” she said.

“I can only feel it. But that’s enough.”

Oanh’s blindness arrived gradually, beginning with blurred vision and ending in total darkness.

At first, she said, she was confused and frightened.

But the emotional weight hit harder in her late teens when it became clear that multiple surgeries had failed.

“That’s when I truly understood what it meant to be blind,” she said.

Determined not to depend on her parents, she moved from the former Long An Province, which is now part of Tay Ninh Province, to Ho Chi Minh City.

There, she found work, housing, and eventually a judo training center.

Para-athlete Trinh Kieu Oanh (L) competes in the under-57kg category at Vietnam’s 2025 National Judo Championship for Athletes with Disabilities in Ho Chi Minh City, September 2025. Photo: An Vi

Her younger sister, Trinh Kieu Nga, often tries to help but says Oanh insists on doing everything herself, from cooking to laundry to navigating public transit.

“She never tells anyone about competitions,” Nga said with a laugh.

“I only found out she was fighting today because I saw the event online and came to surprise her.”

Still, Oanh brushes off praise and rarely dwells on her achievements.

“Yes, people say I’m pretty,” she said, smiling.

“But I haven’t seen my reflection since I was a kid. I don’t know what I look like.”

Oanh’s phone uses a voice assistant to tell her the time.

When it chimed, she stood up abruptly — it was nearly time for her shift at the clinic.

She works long hours, she says, not only to support herself but to save money in case there is ever a chance for another surgery.

“If one day I can see again, I won’t open my eyes right away,” she said.

“I’ll go home and see my parents first.

“The last time I saw them, they still had black hair.

“My little sister was just a toddler.”

A volunteer helps para-athlete Trinh Kieu Oanh (C) put on her belt before a match at Vietnam’s 2025 National Judo Championship for Athletes with Disabilities in Ho Chi Minh City, September 2025. Photo: An Vi

Trinh Mai Thuy Hong, a coach with the Ho Chi Minh City Department of Culture and Sports, has worked closely with Oanh for three years and believes she has the potential to reach international levels.

“She’s always focused, never misses training, and radiates this incredibly positive energy,” Hong said.

She added that judo is difficult even for able-bodied athletes, and for blind competitors like Oanh, it demands even more discipline.

“Many sighted athletes don’t push themselves the way these para-athletes do,” Hong said.

“What Oanh has is something rare — resilience, determination, and the will to overcome.”

Please enter Display Name

Please enter Email

Email Invalid Format

Please enter Email

Email Invalid Format

Incorrect password.

Incorrect login information.

Account locked, please contact administrator.

An error occurred. Please try again later.

Max: 1500 characters

There are no comments yet. Be the first to comment.