The metro is a symbol of modern urban life. Photo: Quang Dinh / Tuoi Tre

While TOD models in cities like Tokyo or Singapore emphasize compact, high-density developments around well-planned metro stations, Ho Chi Minh City faces five critical challenges that necessitate a localized, adaptive version of TOD.

The first challenge is fragmented urban fabric.

The city has evolved through organic, uncoordinated expansion rather than structured, high-density planning.

Residential areas are scattered and socio-economically divided, making it difficult to apply the standard TOD model, where every transit station is flanked by dense, mixed-use developments.

Secondly, the city is facing limited public funding, while large-scale TOD requires substantial public investment in infrastructure, land acquisition, and resettlement.

In Ho Chi Minh City, even funding for metro lines remains a challenge.

As such, the city needs smaller, incremental TOD initiatives that encourage market participation and gradual urban transformation.

Besides, low public transport adoption remains a key concern.

Unlike TOD-friendly cities where people choose to live and work near transit stations, Ho Chi Minh City remains dominated by motorcycles and cars.

Shifting public behavior will take time, requiring not just infrastructure but a cultural transformation.

Another challenge is the complex institutional framework.

Land-use approvals, re-zoning, and investment procedures remain slow, while TOD needs speed and synergy.

Social equity concerns might hinder the city’s TOD strategy.

Without transparent and inclusive planning, TOD could become a vehicle for luxury real estate, displacing lower-income communities.

Equitable TOD should prioritize affordable housing and public services, ensuring that those who most need access to transit are not pushed away from it.

TOD as a regional, flexible ecosystem

Rather than a rigid urban formula, TOD should be seen as a spatial strategy – one that revolves around mobility and adapts to financial, social, and institutional realities.

For Ho Chi Minh City, that means a regionally integrated TOD model tailored to each part’s strength.

This adaptive TOD approach redefines the concept. Instead of merely developing high-rises near metro stations, it seeks to organize socio-economic, residential, and industrial activity along transit corridors – reducing dependence on private vehicles and maximizing land and energy efficiency.

Key features of this regionally customized TOD model include:

Former Ho Chi Minh City should focus on dense, mixed-use TOD clusters around existing and future metro stations such as Ben Thanh, Thu Thiem, and Tan Kien.

It is necessary to link TOD policies with affordable housing and essential public services.

Former Binh Duong Province, serving as an industrial gateway, should develop logistics-oriented TOD zones near industrial parks and inland container depots, while including worker housing, last-mile freight transit, and supporting services.

Meanwhile, former Ba Ria–Vung Tau Province, acting as a port and tourism hub, should create TOD nodes around the Cai Mep - Thi Vai port for smart logistics, and near tourism zones like Long Hai and Ho Tram for eco-urban connectivity.

It is vital to integrate modes like waterbuses and light transit systems to enhance regional mobility.

Under the national merger strategy, which took effect on July 1, new Ho Chi Minh City was formed by merging the old city with Binh Duong and Ba Ria-Vung Tau.

This model also views transit corridors, not just transit stations, as development spines.

TOD becomes a chain of urban catalysts, each tuned to local conditions: social housing, local markets and public services, and logistics hubs where needed.

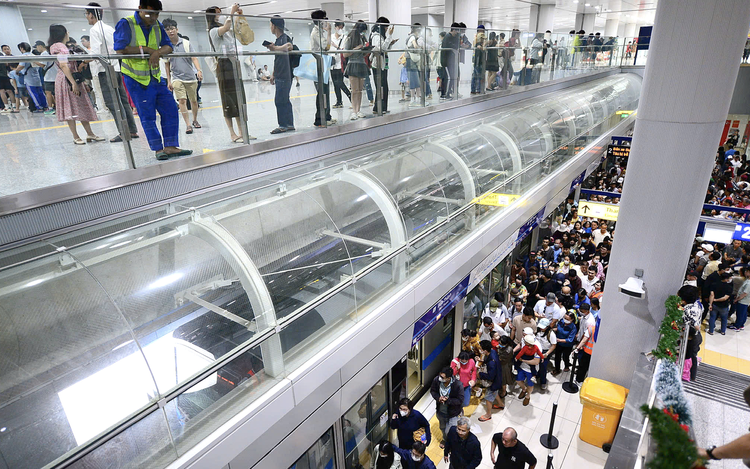

A metro station is crowded with commuters in Ho Chi Minh City. Photo: Quang Dinh / Tuoi Tre

Building foundations for functional TOD

TOD will not flourish in an uncoordinated, vehicle-centric cityscape, but it requires foundational changes such as integrated urban planning, with land use, transport, housing, and public services being planned together.

In addition, successful TOD thrives on foot traffic and daily life.

It needs schools, hospitals, offices, malls, and parks within walking distance of stations, not just commuters, but a resident population.

Moreover, a weak transit system undermines TOD. Without frequent, safe, and well-connected public transport, no amount of station-area development will achieve a meaningful shift from personal vehicles.

Ho Chi Minh City is not a master-planned TOD city like Tokyo, Seoul or Singapore.

It is a complex, historically layered metropolis with limited funding and fragmented development.

Adopting international TOD frameworks without adaptation risks exacerbating inequality and inefficiency.

Max: 1500 characters

There are no comments yet. Be the first to comment.