Photo: Freepik

As climate pressures intensify, so do the risks to Vietnam's food system.

Rising temperatures, saltwater intrusion, and extreme weather are already threatening crops, livestock, and aquaculture.

But as RMIT Vietnam lecturers Dr Tuyen Truong and Dr Tam Le point out, the path to food security in 2050 is not just about defending against loss. It is about transforming how food is grown, processed, and accessed in a way that supports both the people and planet.

Stress on the system

"Vietnam's rice and aquaculture sectors are on the frontlines of the climate crisis," said Dr Tuyen Truong, Program Manager for Food Technology and Nutrition at RMIT Vietnam.

These sectors are of strategic importance to national food security, exports, and rural livelihoods.

But rice-growing areas are shrinking, fresh water is becoming scarcer, and yields are less stable.

Between 2012 and 2022, the area used for rice cultivation dropped from 7.76 to 7.11 million hectares, and could fall to just 6.42 million hectares by 2030.

At the same time, water storage in key regions is as low as 40-50 percent of the design capacity, undermining irrigation systems and crop productivity.

Aquaculture, particularly in the Mekong Delta, is also under pressure.

"Salinity intrusion, water stress, and disease outbreaks are intensified by rising temperatures and erratic weather," said Dr Tuyen.

Vietnam’s rice and aquaculture sectors are on the frontlines of the climate crisis. Photo: Unsplash

Dr Tam Le, a lecturer in The Business School at RMIT Vietnam who has extensively researched the agri-food industry, highlighted broader vulnerabilities: "Climate change disrupts food supply chains and increases post-harvest losses – all of which add cost and instability to the system. These challenges can widen inequality in access to safe and nutritious food for low-income consumers."

For instance, typhoons and floods regularly damage transport infrastructure and delay the movement of perishable goods.

In 2024, Typhoon Yagi alone left more than 95,000 people at risk of food insecurity across 14 provinces in Vietnam.

Dr Tam's research also shows that firms in the food sector are struggling to maintain food safety standards because of climate-induced shocks, rising costs, and infrastructure gaps.

"New foodborne pathogens and scarcer natural resources are forcing firms to rethink their product choices and research and development of hazard control systems," she added.

"The firms that struggle the most with the costs of food safety practices are those with limited capacity to adapt to change."

Systemic shifts for the long term

According to Dr Tam, Vietnam's food security by 2050 will depend on how resiliently the food production transitions and how systemic the innovative practices are.

She highlights three important dimensions for the transition of the agri-food system: (1) development of climate-resilient crop varieties, (2) adoption of low-emission, climate-smart, and inclusive agricultural practices, (3) enhancement of supply chain infrastructure for reduced food losses and quality/safety assurance.

Dr Tuyen Truong and Dr Tam Le. Photo: RMIT

Vietnam has, in fact, made important strides in adopting science-based, climate-smart solutions in recent years.

One notable government commitment is the One Million Hectares program – a plan to establish low-emission, high-quality rice production in the Mekong Delta by 2030.

This includes the use of alternate wetting and drying irrigation, which can reduce methane emissions from rice fields by up to 50 percent.

Low-carbon supply chains are emerging for crops like dragon fruit and seafood.

In the livestock sector, smallholder farmers are using biogas digesters to turn waste into clean energy, reducing emissions and improving sanitation.

Farmers are also adopting integrated rice-shrimp systems and switching to salt- and drought-tolerant crop varieties, which offer both economic and environmental benefits.

"These practices enhance adaptive capacity in salinity-affected areas while improving farmer incomes," Dr Tuyen said.

What the future holds

Food security is not just about availability – it's about accessibility, safety, quality, and resilience.

Looking ahead, the RMIT lecturers believe advanced technologies will play a key role.

AI-powered precision farming, blockchain-based food traceability, and real-time climate risk analytics offer major potential.

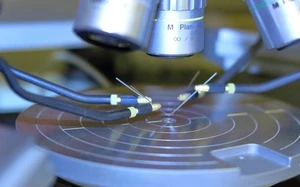

Advanced technologies will play a key role in Vietnam’s food security. Photo: Freepik

Emerging alternatives such as microalgae- and insect-based feed, or even cellular agriculture could also reduce pressure on traditional protein sources while supporting nutrition and sustainability goals.

But innovation alone is not enough. "All these interventions must be nutrition-sensitive. We need to prioritise not just more food, but better-quality diets," Dr Tuyen added.

In addition, ensuring equity and inclusion will be important. This means providing access to technologies, knowledge, and decision-making for women, youth, and smallholders.

By 2050, food security in Vietnam could mean more than avoiding shortages – it could mean ensuring that people in every region have access to safe, affordable, climate-resilient food.

Imagine school meals made with ingredients from low-emission farms, or small urban markets offering fresh produce grown sustainably nearby.

That is the kind of change experts believe is possible if the right steps are taken now.

"What gives me hope is that transformation is already underway. Recent programs and innovations show that Vietnam isn't waiting; it's acting," Dr Tuyen observed.

"The next step is to scale, integrate, and institutionalise these efforts through science, inclusive governance, and sustainability-focused education."

Max: 1500 characters

There are no comments yet. Be the first to comment.