In Vietnam, Dao Van Hoang turns art into voice for nature

From the first sketches in his notebook to hundreds of wildlife paintings, Dao Van Hoang has turned art into a compelling call to protect vanishing species.

Beneath the dense forest canopies of Cat Tien National Park, where Vietnam’s last Javan rhino was killed in 2010, Hoang found the soul of his art.

As a child, he would lie on the floor sketching the animals he saw around his home with chalk and pencils.

He visited the Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens to study the exotic creatures brought there from distant regions.

After years of traveling back and forth to Cat Tien during the 2010s, he knew that wildlife species would become the central subjects of his work.

Edwards’s pheasant (Lophura edwardsi), painted in 2025, a bird once extinct in the wild in Vietnam but now returning thanks to extraordinary conservation efforts

From sketch to storytelling

Hoang does not just paint, he tells stories. Field trips to national parks and remote forests across Vietnam, often alongside conservation scientists, have been his main source of inspiration.

There, he sketches animals, observes the environments where they hide and survive, watches how light filters through the foliage, and attempts to recreate the fleeting presence of endangered creatures.

His small sketchbooks are filled with bird heads, animal limbs, stretches of forest, cliff formations, scientific notes, and geographical references.

One of his works portrays the elusive saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), a mysterious species native to the Annamite Mountains.

'Deep Pool,' a painting of the saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), created in 2015

Relying on rare photos and his imagination, he brought the animal back to life in a nocturnal forest scene where flickering light serves as a gentle reminder of life’s fragility.

At Le Petit Musée, his studio in Thao Dien Ward, Ho Chi Minh City, his paintings are neatly stacked, awaiting their first domestic exhibition.

Hoang has experimented with a wide range of techniques and materials: acrylic on canvas for large-scale works, watercolor for quick sketches, and digital tools for scientific illustration.

What makes Hoang’s art stand out is his ability to combine scientific precision with emotional depth.

“I studied the proportions, behaviors, and habitats of each species carefully, working closely with conservation scientists. If I got it wrong, they wouldn’t let me off the hook,” he joked.

His animals are always depicted in detailed natural landscapes true to their habitats -- a lesson he attributes to Canadian master painter Robert Bateman, a global influence in wildlife art whom Hoang deeply admires.

But while Bateman is known for using light and shadow to create dramatic depth, Hoang places more emphasis on the subtle movements of animals within their natural worlds.

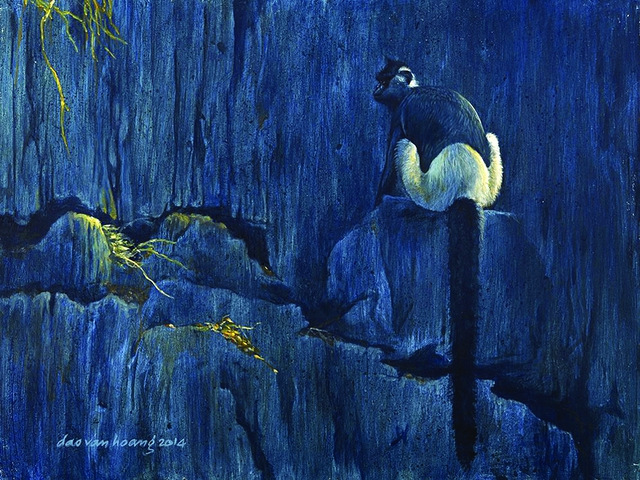

Delacour’s langur (Trachypithecus delacouri) at Van Long Wetland Nature Reserve in Ninh Binh Province, northern Vietnam.

Art as a bridge

In August 2014, when Hoang heard about a conference hosted by the International Primatological Society in Hanoi, he reached out to the organizers and offered to display 22 of his primate paintings.

“I wanted to make the conference more accessible, not just all about science,” he explained.

That simple gesture became a turning point in his life: “It was the first time I started thinking of myself as an artist.”

Since then, he has brought his works to audiences in the U.S., Thailand, and Europe, often alongside scientists advocating for conservation.

“Most of my wildlife art is about hope, the hope for a better, more sustainable environment,” Hoang said.

His work demonstrates how art can transcend aesthetics to become a call to action, reminding us that each species is a vital piece of the larger puzzle of life on earth.

“If someone sees a painting, feels something, and begins to love it, maybe they’ll love the creature in it too. And when you love something, you’ll want to protect it," he said

A 2022 painting of the large-antlered muntjac, based on black-and-white images from camera traps

Hoang was once commissioned by the World Wide Fund for Nature to paint the flora and fauna of Cat Tien National Park on a 200-square-meter wall.

Though that mural no longer exists, a few years later he created another large-scale work featuring life-sized images of elephants, rhinos, tigers, gaurs, bears, and primates, this time funded by Free the Bears, also at Cat Tien.

He also designed an exhibition center for Wildlife At Risk at their wildlife rescue center in Cu Chi, a rural region in the northwest part of Ho Chi Minh City, painting a 14.5-meter-tall, 9-meter-wide mural of a sarus crane.

Another large-scale work connected with HIV clinics at the Ho Chi Minh City Hospital for Tropical Diseases features ocean-themed imagery.

He wrote and illustrated a children’s field journal called Exploring Nature with a Pencil for Bidoup Nui Ba National Park and runs the 'Nature, Art & Fun' program at Le Petit Musée.

The life of this self-taught artist continues along the path of using brushstrokes to preserve the images of rare and endangered species in the hope of awakening a love for nature in every viewer.

The artistic secrets behind Hoang’s wildlife paintings

Hoang favors the glazing technique, using thin, translucent layers of color that allow him to recreate the profound depth of ancient forests, the flickering motion of wildlife, and the delicate transitions of natural light found in wild spaces.

“I’m captivated by animal coverings -- furs, scales, and feathers -- these vivid textures shaped over millions of years of evolution,” he said.

“I want to understand how those structures work, how they move.

"The more I observe, the more I discover.

"The more I paint, the deeper I immerse myself in every detail, every line, every tiny miracle.

"I’ve seen rippling muscles beneath fur, light caressing individual feathers, winds shifting the shape of life.

"Nature is the true master artist. I simply follow its brushstrokes.”

Thuy Tien - Kim Thoa / Tuoi Tre News

Link nội dung: https://news.tuoitre.vn/in-vietnam-dao-van-hoang-turns-art-into-voice-for-nature-103250802171852853.htm